A short while ago, I tripped across an article in Mother Jones by Shane Bauer entitled Your Family’s Genealogical Records May Have Been Digitized by a Prisoner.

I’ve long enjoyed the insightful pieces this publication offers and was pleased to see this particular topic being addressed, but as a professional genealogist, I felt that a few key aspects were understated or left out. Reading the article, one could be left with the impression that the primary mission in this undertaking is retroactively baptizing ancestors into the Mormon faith – and that’s undoubtedly part of the motivation – but the fact that millions of us, regardless of faith, benefit from these records as they are made available free online at FamilySearch deserves greater emphasis. Nor does the website wait for records to be indexed to make them available. If you don’t mind clicking through a few dozen pages of records to find that circa 1876 marriage of your great-great-grandparents, you can probably search digitized images now.

Then there’s the matter of the baptism itself which has been a controversial issue for decades. Many feel otherwise and I understand their conviction, but as a Catholic, I don’t mind for the simple reason that I don’t subscribe to Mormon beliefs. If someone chooses to “seal” my Roman and Greek Catholic ancestors, this doesn’t disturb me because my belief system tells me that they retain the religion they practiced in life. From my perspective, my Roman Catholic ancestors who lost their lives or fled their homeland as a result of the Irish famine are no less Catholic because someone performed a ceremony on their behalf a century and a half later.

And frankly, I’m grateful to have access to their records because they help me learn about my ancestors. The Greek Catholic church records for Osturna, Slovakia (available on Family Search), home to all the Smolenyaks in the world, for instance, shed light on forebears I would otherwise remain ignorant of. I can peek into their lives, grieving after the fact for the loss of three children in rapid succession and watching the trail of orphans that the epidemic left in the village, but also celebrating the bursts of marriages just before or after each harvest season – and the crop of children that inevitably appeared nine months later.

The article also insinuates that the prisoners are being exploited. There’s no mention, for example, of the “Fuel the Find” initiative which was held last week with the aim encouraging 100,000 volunteers to do exactly what the inmates are doing.

And finally, for many inmates, this is more than just an opportunity to get out of their cells for a while. As substantiation, I offer this piece (excerpted from Honoring Our Ancestors) I wrote in 2001 (the program has been around longer than mentioned in the article) attempting to capture my interview with Blaine Nelson, one of the inmates then indexing records.

Second Chances

Before prison whenever I heard a set of keys rattling, I would think of a small child in church whose mother was trying to keep him or her quiet. Now that I’m in prison, there’s a whole new meaning to that sound. To an inmate that jangling means confinement, handcuffs, or an officer coming. Best to stop whatever you’re doing and act like you’re asleep.

After eleven years working on the Freedman’s Bank Project, I often find myself wondering what the sound of keys meant to slaves. Do you think that they too knew that the rattling of keys meant shackles and handcuffs?

One of the worst fears in the life of an inmate is being told, “Roll up, you’re moving.” Moving to a new housing unit is very uncomfortable because it means leaving old friends behind and not knowing what awaits you. I bet that slaves felt the same anxiety when a new wagon or a stranger pulled up on a plantation. I believe that they felt it even more so, because to them, it meant being sold or the loss of one of their loved ones. We inmates know what it’s like being away from family, but our situation is usually temporary. For slaves, the separation was forever.

So what is this Freedman’s Bank Project that has me trying to put myself in the shoes of slaves? Back in 1865, the Freedman’s Bank Savings and Trust Company was established to help recently freed slaves with their financial dealings. It was supposed to be a safe place for them to deposit their money and protect it from swindlers, but due to bad management and just plain old fraud, the bank collapsed in 1874. More than $57 million in deposits was lost, dashing the hopes and dreams of the thousands who had trusted the bank.

The only good to come out of this was the records of the depositors. In order to open an account, a person had to give a lot of information, such as names of family members, places they had lived, and even details about relatives sold to other locations. Some eight to ten million African-Americans have ancestors listed in these records, making them very valuable for those interested in tracing their roots, especially since there are so few records pertaining to slaves. The problem was that these records were never indexed in any way. With hundreds of thousands of files, it was unrealistic to even try to search for your family in them.

That’s where we inmates come in. Back about a decade ago, I was one of four to enroll in the first genealogy class taught in the Utah State Prison system. One thing led to another and the South Point Family History Center was established in the prison. Although it was created with the assistance of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints, the program is voluntary and open to people of all faiths. All inmates are eligible to participate as long as they honor center policies, such as not using bad language.

I was a diesel mechanic when I came to prison and hardly knew what a computer was, but I soon found myself serving as a project coordinator and becoming very skilled with computers. Word about the center spread and enthusiasm ran so high that it became difficult for me to schedule film reader time. Some inmates, while waiting for their allotted hour on the machine, were even seen holding up their microfilms to the light in an attempt to read them.

Shortly after the center opened, we were asked whether we might be able to help with some extraction projects, the idea being to transcribe and index information from microfilms so it would become more accessible to researchers. We immediately agreed.

During the 1990s we worked on a number of projects, but it was the Freedman’s Bank Project that meant the most to us. And it was no small task. Eleven years, six hundred inmates, and over 700,000 volunteer hours later, some 480,000 Freedman’s Bank records had been extracted and indexed. What’s in these records? Here’s one example:

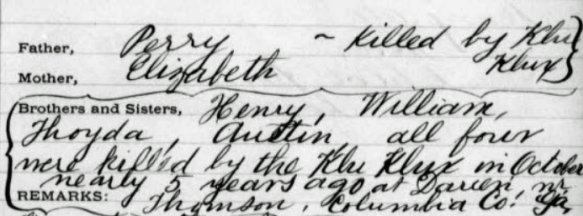

Record for: Perry Jefry

Date: July 31, 1875

Where Born: Warren County, Georgia

Residence: Campbell Street on Savannah Road

Age: 24

Occupation: Mattress making and cooking

Father: Perry, killed by Ku Klux Klan

Brothers and Sisters: Henry, William, Thoyda, and Austin. All four were killed by the Ku Klux in October nearly five years ago at Darcen near Thomson, Columbia County, Georgia

Before we started, I had no idea the impact this work would have on me and the other inmates, but how can you work with records like this and not feel compassion? Even the toughest of us shed some tears when we saw how these people had been treated and what events took place in their lives. Time and time again, we found comments like:

“My father was sold.”

“Brother killed, shot to death.”

“Had a sister, she was burned to death.”

“Father killed when I be little, crushed by wagon.”

One record that will stay for me the rest of my life said, “I do not know what my daughter’s name is. She was taken from me at birth and traded for some field tools.” For me, one of the most important days of my life was when I held my first newborn daughter in my arms. I was just so happy. I could not even begin to imagine what it would be like watching her traded for a handful of garden tools.

These records were teaching me compassion, empathy, sorrow, and concern for others. After each session I would go back to my cell and wait until the lights were off and I was alone. Then I would cry because there was a time when I too mistreated people.

And I wasn’t the only one affected. One Sunday when we were working on the records, I saw that the inmate sitting next to me was crying. When I asked him if he was all right, he sniffled that he just couldn’t believe how these people were treated. I reached out to comfort him and as I touched his shoulder, I noticed a tattoo on his neck that read KKK.

I really believe that God waited until now to have this work rediscovered because he knew what a great effect it would have on all those who worked on it. And while we can’t compare our circumstances to theirs, I think that being in prison helped us relate to the slaves better than if we had done this work on the outside. In some small way, I feel as if we have given these silent voices a second chance to be heard, and we in return have been given our own second chance.

When the New Orleans Volunteer Association (NOVA) began typing State of Louisiana vital records into Rootsweb database, we learned the original typed ledgers we were working from were created by state inmates as part of typing skill training while they were in prison. Having worked with the indexes and the documents behind them for many years now, I must say the accuracy of the typed ledgers (spelling of names correctly, no transposition of numbers, etc.) were much more accurate than I find in the “for pay” research sites. The closer the transcriber is to the original record produced, they know the nuances of names and places, and the indexing is more accurate. Glad you posted this article. It gives even more depth to the real need for accuracy in research which not only gives you your own family history, but the background against which it occurred. Paints a very three dimensional picture which can amaze and startle.